Follow me as I move to Vermont, consult a life wizard, quit my marketing career, and test the adage, "It's never too late to be what you might have been." If you find something that strikes you, please share this newsletter with your reinventing, resilient, slightly rebellious friends.

“Learn to type, and you’ll always have a job,” my mother said.

This was 1978, and I was a junior in high school—the year I was meant to have figured out what I was meant to be. At age sixteen, I was supposed to outline the narrative arc of the rest of my life.

What did I know?

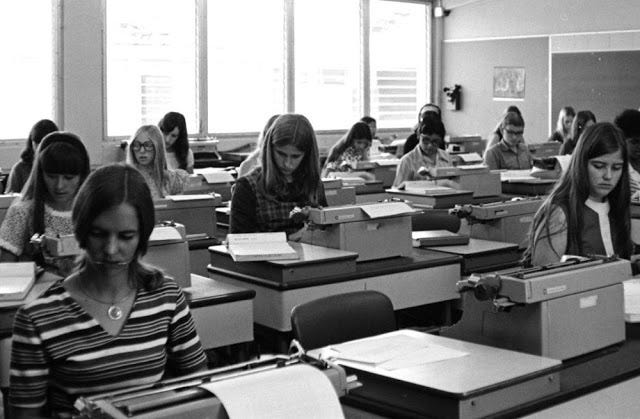

In typing class, we clipped our lessons to metal stands and pulled our shoulders back, fingers poised over the home row of the bulky manual keyboard—asdf jkl;

I kept my knees together and my feet flat on the floor. With a glance around the room, I’d assess my words-per-minute competition—mostly girls, all of us typecast as one kind or another: cheerleader, jock, band geek, burnout, slut, nerd.

The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.

Mrs. Strickland1 dictated. Ka-thunk, the sound of twenty-four Underwood carriages, followed by peck, peck, peck in varying rhythms. The race to finish. The quest for perfection. The satisfying zzzzzwack of the carriage return. Do you remember?

They call it keyboarding now, but how much has changed?

“Eyes on your lessons, not your fingers!” Our typing teacher watched us closely over her mother-of-pearl cat’s eye-glasses. The day after she caught me with my head down searching for the correct letters, I returned to class to find every key hidden by a dollop of crimson nail polish.

I think I can still smell her, Mrs. Strickland, a whisper of talcum powder, lilacs, and cigarettes. In my mind, she is wearing her uniform of ruffled blouse, cardigan sweater, and a skirt made of tartan from our town’s last woolen mill. To me, she is frozen in time.

Practice makes perfect.

J J J space. F F F space. I hate making mistakes. Back then, they were harder to correct.

Using the tiny bottle cap brush to dab the chalky Liquid Paper over my mistakes was a delicate task. Too much left a bubbly clump on the page, smearing any effort to try again.

Did you know a typist invented Liquid Paper? Bette Nesmith Graham, also known as the mother of Mike Nesmith—the tall, quiet guitar player in The Monkees—was a single mom who supported her children as an executive secretary at the Texas Bank and Trust. She was also a talented artist, which is how she came up with the idea of painting over mistakes instead of erasing them.

I can guess what Bette heard when she sat behind her typewriter and when she moved to the corner office. You’re too bossy, too cold, too tense, a bitch. You need to learn how to take a joke. Lighten up, for God’s sake. Gee, Bette, you’d be prettier if you smiled more. I’ve heard them all.

In 1958, Bette started her own company, then sold it twenty years later for $47.5 million. She died one year after that—at age fifty-six.

At fifty-six, I was still typing.

The font remains the same.

The State Department ditched Times New Roman for Calibri (though the stalwart serif is still preferred for literary submissions). Gen Z thinks CC stands for Closed Captions, and photocopiers are perpetually jammed. If photocopying even exists—I haven’t been to an office for a while.

In typing class, we used fragile inky sheets of carbon paper to make copies. Mrs. Strickland insisted on reusing the inky sheets, sweeping past our tables to collect a wrinkled stack with her red-polished fingers. Like most teachers today, I guess she purchased many classroom supplies with her own money, and it’s likely too—because it’s still true—she was paid less than the male teachers at Messalonskee High.

Mrs. Strickland taught us how to prepare correspondence. We typed cc: and listed every intended recipient, then signed our names in ink. It’s hard to imagine now when robots write copy that reaches millions of people, but communication used to be personal.

We addressed our business letters to Mr. Jones (Not Miss or Mrs. Never Ms.) and folded the sheet into thirds. The first fold had to be slightly larger than the second, making it easier for the recipient to grasp and unfurl with one hand. I pictured Mr. Jones holding a cigar in the other.

When I graduated from high school in 1980, two women held the title of CEO in the Fortune 500. Forty-three years later, there are fifty-two. (I’ll leave that right there.)

I write this digital post using an app I downloaded from the cloud. Words appear and disappear on my bright flat-screen monitor as fast as I can move my fingers. Programmers I’ve never met anticipate and correct my errors before I realize I’ve made a wrong move.

At sixty-one, I only type for myself—becoming the writer I never knew to dream I could be at sixteen—or eighteen or twenty-two. Most days, it feels like I backspace more than I move forward, but I am less afraid of making mistakes.

I wonder, though, would I still write if it meant depending on a mechanical hammer to strike letters onto a blank sheet of paper—clacking out each thought as slow as progress?

Work hard. Be brave. Believe.

Catherine

Try the Substack Notes App

If you’re not using the Substack app yet, please give it a try. More access to other great writers AND less clutter in your email inbox. Learn more.

Eldora Strickland was an admired and accomplished educator.

"The brown fox jumps over the lazy dog" was like a time machine - holy cow. Nailed it. Raised three (now young women) to think as business owners who will hire a CEO :) Think brave and never be afraid to break things - especially old systems. Love your work.

“I wonder, though, would I still write if it meant depending on a mechanical hammer to strike letters onto a blank sheet of paper—clacking out each thought as slow as progress?” I have wondered that same thing! Oh! And remember how hard it was to correct typos with those sheets of paper”Ko-rec-type?” Just the fear of making a typo on an assignment ensured that I would make several. A nightmare. I love technology. lol